Kim Moser

Kim Moser is an American born artist who was raised in the borough of Manhattan in New York City where they produced the majority of their oeuvre in a variety of media, most notably photography, with early works in black-and-white and later in color.

Early Work

Some of Moser's first works were sculptural, produced by arranging wood blocks to create a variety of freeform structures. During an early encounter with the American artist Donald Judd in the mid-1970s, Moser visited Judd's studio on Spring Street but the two quickly had a falling out after Judd saw Moser climbing on one of his pieces and remarked, "Don't sit on that; that's art," thus dashing any chances of the two artists forging a collaboration. Judd never spoke publicly about the incident, and to this day critics are divided over whether Moser's act was one of an enfant terrible or an aptly prescient gadfly.

Several years later, Moser pivoted to physically constructing entire pieces from wood by sawing, sanding, gluing and nailing, while studying with noted American painter and educator Ed Kerns, who himself became the subject of at least one photo collage created by Moser.

Drawings

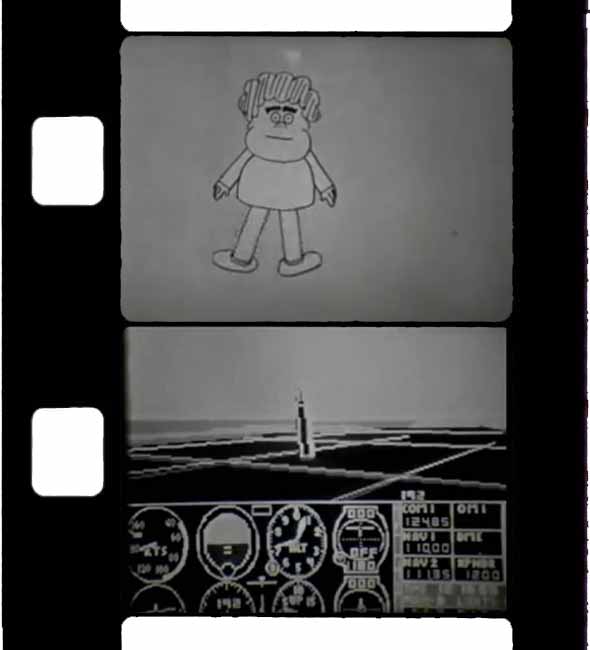

Around the same time, Moser began experimenting with drawing images on paper using various forms of writing implements: pencil, ballpoint pen, fountain pen, marker, and occasionally crayon, eventually incorporating less conventional media from a nearby photo lab such as grease pencil, photographic film in different formats (35mm and 110), Rapidograph pen, and even photographic paper.

Moser's first abstract drawings eventually gave way to a cartoon style, leading Moser to create several series of underground comic strips (Barf! Comix, Crud Comics, Blurtch Comics, and more), most of which grappled with the boundaries of societal norms.

Studio Relocation

In the early 1970s, Moser moved to Union Square, occupying a soon-to-be landmarked brownstone building rumored to be the location where former president Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt had purchased his glass eye several decades earlier. This period, coincidentally (although some consider it a strategic decision) located near pop artist Andy Warhol's Factory provided a fertile Bohemian enviromment, and Moser produced many iconic works here, including a series of Super-8 movies and animations. While there is no record of Moser ever having met Warhol, it is well known that Warhol occasionally had black-and-white film developed by the commercial photo lab where Moser occasionally worked, located on the ground floor of Moser's residence, and it would not be unreasonable to assume that at least one of the artists may have been subtly influenced by the other's work.

The readily available black-and-white photo lab provided Moser with the opportunity to produce a notable series of photograms made with several types of photographic paper, simple art supplies, and a photographic enlarger, resulting in a fresh take on the "found art" movement.

One of Moser's first works to gain widespread acclaim was a series of candid photos of students and teachers at work and play at a local school. Characterized by the use of natural light and low angles to match the subjects' heights, as well as an unbiased take on the surrounding environment, these photographs have been hailed as perhaps the most unflinching, intimate view of experimental private education to date, securing Moser's position as darling of the art world.

Street Photography

An early and prolific street photographer, Moser has been known for carrying a camera nearly everywhere, decades before street photography became commonplace and nearly half a century before ubiquitous cell phones were the norm. Moser's earliest known photographs were taken in the early 1970s, and it was during the fertile phase of the ensuing decade that Moser's vision emerged, quickly showing signs of a maturing artist.

A fascination with the Consolidated Edison building visible directly outside their studio window led Moser to produce Con Ed: a Study in Power, a series of photographs of the building's façade, considered to this day to be the definitive decades-long study of the iconic building. Despite the duality of the building—loved by many for its architectural style while simultaneously reviled for embodying the headquarters of a monopolistic bureaucracy—critics universally agree that Moser's photographs of the controversial structure are unparalleled, and reconcile the inherent tension with a tenderness rarely seen in architectural photography. The reverential undertones of photos by notable New York City architecture photographer Edmund V. Gillon, Jr. perhaps come closest; although hardly surprising when one considers that Gillon had met Moser on several occasions in the late 1970s.

Moser kept up regular correspondence with noted artist and art critic Eve Medoff, who encouraged Moser to keep a scrapbook, or "morgue," of images. This suggestion, along with Gillon's gift to Moser of his book Picture Sourcebook for Collage and Decoupage (among others), may have fueled Moser's experiments in collage and découpage.

Animation

Moser's interest in animation began with the acquisition of a Super-8 camera in the late 1970s, leading to an intense period of output, including several hours of animation using a variety of methods: traditional cell animation, découpage, claymation, and even direct (distress) animation, in which Moser painstakingly altered individual frames.

Computer Graphics / CGI

An pioneer in computer graphics (CGI), Moser created animated works using both digital computers and analog movie film in the early 1980s. This juxtaposition of different generations of media, while typical of CGI from that period, was taken to an extreme by Moser's experiments, including their now famous short Buzzing the Twin Towers in which Moser "flew" an early flight simulator between the World Trade Center buildings, eerily foreshadowing by several decades the tragic events of 9/11.

Multimedia

As new technologies became available in the ensuing decades, Moser seamlessly embraced and incorporated many of them into their works, while never straying far from their roots. Super-8 movie film gave way to video, first recorded on VHS and, later, a dedicated digital 8mm video camera. Photographic film yielded to electronic images, first with digital cameras and then cell phones—although Moser, always the traditionalist, prefered the use of dedicated cameras to crude digital telephonic devices. This "new media," as it was known at the time, made it possible for Moser to preserve, remix, and reuse some of their earlier works, such as digitizing negatives and film for use electronically.

Silver Screen

While usually preferring a photographer's traditional position behind the camera, Moser's most well known appearance on the silver screen was a 1992 cameo in the film Bad Lieutenant opposite Harvey Keitel, in which Moser played a bystander (uncredited) at a crime scene investigation. Fans note that this appearance gave Moser a Bacon number of three (Moser in Bad Lieutanant with Keitel → Keitel in Smoke with Forest Whitaker → Whitaker in The Air I Breathe with Bacon), although Moser already had several instances of a Bacon number of two via earlier connections to friends and family members.

Latest Works

Moser continues to take photographs, usually in concentrated bursts of creativity while out and about in New York or other locales. The subject material has changed dramatically from Moser's early photographic years: while in the past the photos were largely of inanimate objects (buildings, vehicles, signs) taken in black and white, today they tend to be color images of people, celebrating the humanity within us all.

No stranger to technology, Moser embraced photo editing tools decades ago and these days enjoys using the computer to combine and alter images, often incorporating prior works. The Internet has also opened a new venue to expose Moser's art to a new audience, and every highly anticipated release of one of Moser's images sends the digerati into a flurry of discussion and analysis.

Influences

While Moser has traveled in the same circles as other well known artists, there is little signs of their influence on Moser's work. A staunch individualist, Moser prefers to eschew other artists' styles, trying instead to create a look that stands on its own. On the rare occasion that another artist's style can be found in a Moser work, it is less Zeligian and more Gumpian in nature, as Moser has a tendency to effortlessly co-exist with other artists' styles rather than merely duplicate them.

Common Themes

While Moser's work spans a huge range of styles, media, and time, there are several recurring themes that Moser never strays too far from. No one would deny that Moser has one foot firmly in the realist camp, while the other often dabbles in the whimsical, giving the viewer the opportunity to glimpse the absurdity in even the most mundane situation. This tendency to highlight two polar opposites, in varying proportions, results in Moser's (perhaps unintended?) sly nod to the viewer being the ultimate arbiter of what they are seeing.

While other artists often give little thought to the influence of contemporary events, Moser's manifold relationship with the zeitgeist forces the viewer to grapple with whether Moser's art is merely "of the time" or actually "timeless," an open-ended question which Moser holds up as a mirror to the viewer.

When asked to explain their work, Moser usually demurs, preferring the viewer to draw their own conclusions. As Moser was once quoted as saying: "Any way you interpret it, you're wrong."